Execution under constraint: how procurement secures delivery, resilience, and value

2025 was another year of heightened uncertainty for the energy sector. Geopolitical volatility, shifting trade regimes, accelerating regulatory pressure, and rapid advances in digital technologies continued to reshape market conditions. At the same time, the sector demonstrated a notable degree of resilience. Energy companies continued to invest at scale, even as cost pressure, supply-chain complexity, and execution risk increased across infrastructure, generation, and networks.

The energy sector enters 2026 defined by execution under constraint. Rising demand, sustained infrastructure investment requirements, and tightening sustainability expectations collide with capacity bottlenecks, geopolitical fragmentation, and structurally elevated cost levels across supply chains.

These challenges are not new – but they have not eased. Instead, they have become structural. In this environment, capital availability alone no longer determines success. Delivery, resilience, and competitiveness increasingly depend on how effectively organizations secure supply, manage risk, and actively balance cost, resilience, and carbon trade-offs. Across recent energy programs, we consistently see execution risks materialize not in funding decisions, but at procurement-led interfaces: between suppliers, engineering, and delivery organizations.

Meeting these demands requires more than incremental optimization. It requires a continued transformation of how procurement operates – across capabilities, decision rights, and its interfaces with engineering, operations, and finance. The following five trends highlight where C-level leaders must focus in 2026 to ensure execution and long-term value in the energy sector.

Supply chain sovereignty remains a defining strategic constraint

Supply chain sovereignty continues to shape procurement decisions across the energy value chain. Trade policy, local-content requirements, tariffs, and subsidy regimes remain decisive factors for grid equipment, renewable components, and critical materials. While localization can reduce geopolitical exposure and improve regulatory alignment, it often comes with higher cost and limited available capacity. The tension between cost competitiveness and supply security therefore remains unresolved. What has changed is procurement’s role: from managing trade-offs reactively to structuring them deliberately through total cost, risk, and delivery lenses.

Demand for renewable energy equipment continues to rise. Wind and solar installations are still growing globally. At the same time, equipment costs remain elevated following the supply-chain disruptions and inflationary pressures of 2022 and 2023.

Across many energy categories, the cost impact of sovereignty-driven sourcing is now tangible. Industry analyses show that bringing major wind components onshore can increase costs by roughly 20–100%, depending on component complexity and manufacturing maturity. These uplifts reflect higher labor costs, logistics constraints, lower economies of scale, and the need to build domestic capacity from a limited base.

Structural dependencies continue to shape these supply chains. More than 90% of rare earth magnets used in wind generators, motors, and electrification systems are produced in China, creating concentrated exposure that cannot be diversified quickly. Domestic production of heavy castings and large bearings remains limited in both the United States and Europe, with new facilities requiring substantial capital investment and multi-year timelines to establish.

Workforce constraints add further pressure. In critical trades such as foundry work, labor availability has been shrinking by around 2% per year, even as clean-energy manufacturing demand continues to grow.

At the same time, market conditions are becoming more differentiated. While some categories remain structurally constrained, capacity additions in others are easing supply–demand imbalances and increasing margin pressure on suppliers. Procurement must actively distinguish where leverage exists – and where it does not – and translate that insight into category-specific sourcing and negotiation strategies.

Leading organizations continue to reshape supplier portfolios, support onshore capacity development through long-term agreements, and accelerate qualification in close coordination with engineering. Where this is done early, companies are better able to stabilize pricing and delivery; where it is delayed, sovereignty becomes an additional cost driver without commensurate resilience gains. These choices are not temporary responses; they define long-term cost positions and risk exposure across energy portfolios.

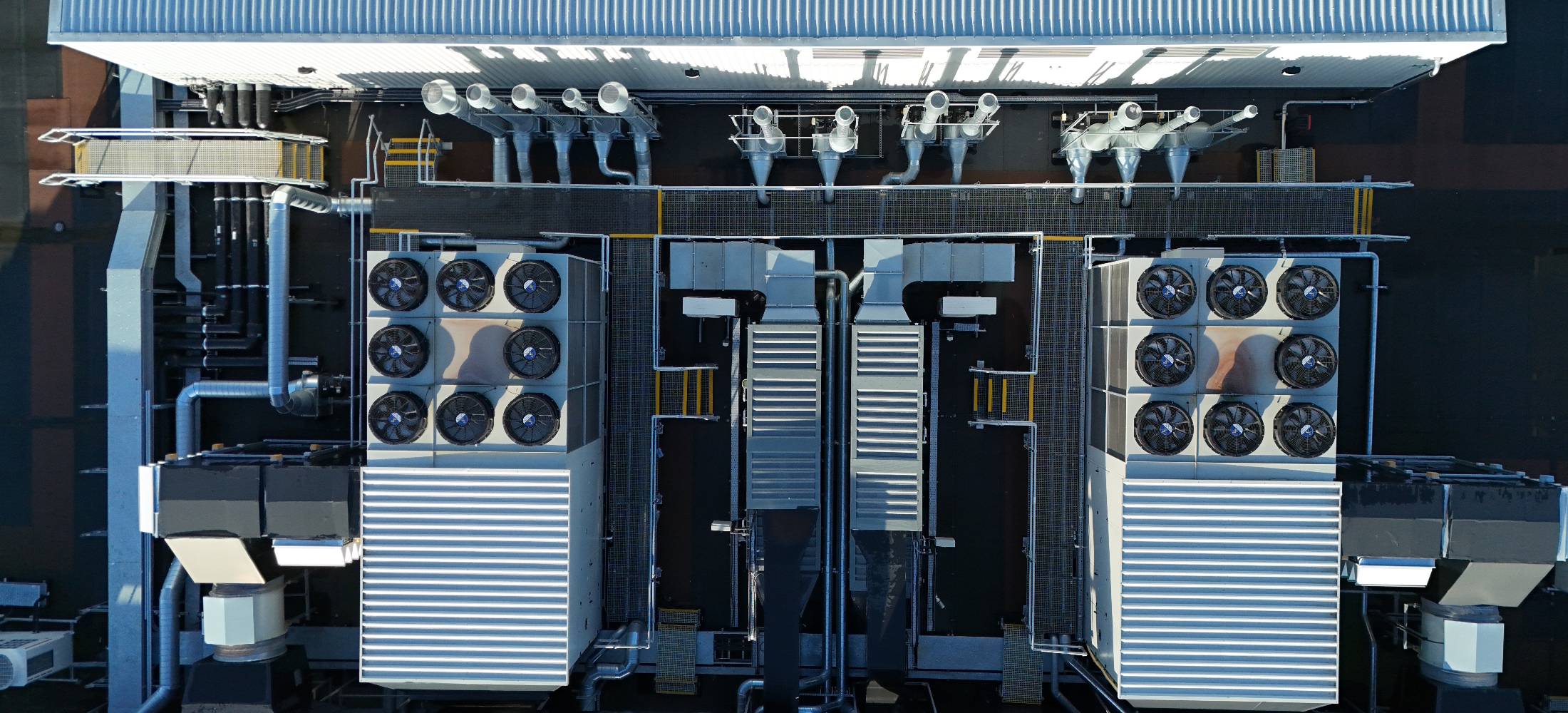

Execution pressure intensifies as procurement orchestrates increasingly complex supply chains

Demand for power is projected to rise by more than 3% annually through 2026, with data centers alone expected to consume over 1,000 TWh by 2026, up from 460 TWh in 2022. The growth of data centers and AI workloads, alongside electrification and grid expansion, is driving unprecedented pressure on energy infrastructure. Capital is available – but execution capacity is not. In this environment, supply chains are no longer a downstream consideration. They increasingly shape infrastructure design itself. Scarcity of key materials, limited manufacturing capacity, and competition across Energy & non-Energy projects force difficult choices long before construction begins.

Concrete bottlenecks are already visible. Copper availability is tightening across grids and electrification projects. Meanwhile, project complexity is rising. As the wind sector has shown, inconsistent specifications, fragmented engineering models, and a lack of standardization can erode performance at scale. At the same time, local content rules and reshoring mandates in the U.S., Europe, and India are testing domestic manufacturing capabilities and constraining supplier. It’s a problem of complex and still multiplying dimensions, driving execution challenges and the ability to deliver on-time, and at cost.

Procurement’s role has changed as a result. It is no longer about running sourcing events for individual projects. It is about coordinating complex supply chains across technologies, regions, and timelines. Without early coordination, projects are locked into designs that the supply chain cannot deliver at scale. Lead times stretch, alternatives are limited, and execution risk is pushed downstream – where it becomes far more expensive to manage.

Beyond headline Capex projects, procurement teams are managing larger and more complex portfolios, with growing exposure to physical logistics, global coordination, and operational continuity risks across the asset lifecycle. High-performing organizations embed procurement early in project development, engage suppliers pre-FID, standardize specifications, and rely on framework agreements for critical equipment to stabilize delivery.

EPC scarcity continues to reshape power, partnerships, and behavior

EPC capacity constraints remain a defining reality across the energy sector. Skilled labor shortages, sustained project pipelines, and increasing technical complexity mean that

This imbalance is particularly visible for new energy technologies and first-of-a-kind projects. Small modular reactors (SMRs) are a clear example. More than 120 SMR designs are currently under development globally, yet most EPCs continue to prioritize utility-scale, repeatable work over technologies with higher technical risk and uncertain delivery economics. For newer developers, this creates a structural disadvantage: limited scale, higher perceived risk, and less bargaining power when competing for EPC attention.

As a result, traditional leverage-based sourcing models remain insufficient. Securing execution capacity depends on being perceived as a credible and attractive client – with realistic timelines, coherent demand signals, and stable project pipelines.

In this environment, no single organization can act alone. Across the board, developers are moving upstream. They partner earlier with OEMs, construction firms, and in some cases even customers to secure critical capabilities, align on specifications, and reduce perceived delivery risk before EPCs are formally engaged. This shift is increasingly visible in emerging technologies, where early ecosystem alignment can determine whether a project ever reaches execution.

At the same time, procurement discipline remains essential. Being a “customer of choice” does not mean abandoning commercial rigor. Leading teams deliberately differentiate their approach: partnering where capacity is scarce, while actively challenging suppliers and recovering margins in categories where market conditions allow leverage.

AI starts delivering value – where organizations move beyond pilots

Utilities and energy players are moving from experimental AI pilots to embedding AI into core processes. In recent years, many electric and gas utilities have invested $500M–$1B each in technology-driven transformation across customer operations, finance, asset management, and supply chain and procurement, as they increase infrastructure investment (BCG Global).

The challenge today is not access to AI, nor skepticism about its relevance. It is how to harness AI deliberately – focusing on the right use cases, deploying them at scale, and tying them to measurable outcomes such as cost reduction, productivity gains, and operational resilience.

AI’s strongest impact sits at the intersection of field operations, sustainability, and procurement. Network operators increasingly use data and AI to decide which work truly needs to be done (“do the right work”), which resources and suppliers to deploy (“use the right resources”), and how to execute tasks most efficiently (“do the work right”). When applied together, these levers have been shown to reduce work volumes by roughly 10–30%, lower resource costs by around 10–15%, and improve productivity per unit of work by 20–30%.

In practice, this includes AI-optimized crew scheduling, vegetation-management planning, predictive maintenance for grid and renewable assets, and materials planning aligned with asset risk. These use cases often require contractors and suppliers to operate within shared digital workflows, increasing transparency, accountability, and performance across the supply base.

For procurement, the most visible AI impact is in smarter supplier management and commercial decision-making. AI can read and compare complex EPC and equipment bids at scale, surface non-obvious specification trade-offs, and power should-cost models across labor, contractor services, and materials. In selected workflows, AI-enabled sourcing and supplier analytics have delivered savings in the range of 15–30%, while also reducing reliance on third-party spend.

The differentiator in 2026 is not technology access, but execution discipline. AI creates value where organizations build strong data foundations, prioritize a small set of high-impact use cases, and align procurement, engineering, and operations around shared metrics. Where deployment stalls at pilots or dashboards, value remains elusive. Where execution is disciplined, AI becomes a force multiplier across cost, productivity, carbon, and resilience.

Carbon accountability remains unresolved – and commercially relevant

Decarbonization pressures continue to intensify. Regulatory requirements, evolving subsidy frameworks, and investor expectations ensure that carbon remains a commercial variable rather than a narrative ambition. What has changed is not the direction of travel, but the level of scrutiny. Carbon targets are increasingly translated into procurement requirements, contractual obligations, and reporting expectations, often before organizations have reliable data or clear levers to influence outcomes.

In practice, carbon accountability is increasingly enforced through commercial and contractual mechanisms rather than voluntary reporting. In Europe, policies such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) are beginning to translate emissions into direct cost exposure for materials critical to energy infrastructure, including steel, aluminum, and concrete. In the United States, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and related subsidy frameworks continue to shape sourcing decisions indirectly by linking eligibility and economics to domestic content and emissions performance.

For procurement teams, this means that carbon requirements are no longer abstract. They show up in tenders, contracts, and supplier scorecards, often before organizations have fully mature Scope 3 data, clear governance, or aligned decision rights in place.

Procurement remains central to this challenge. Scope 3 transparency requirements, supplier engagement, and data quality improvements are ongoing priorities. At the same time, affordability constraints force disciplined decisions about where decarbonization efforts deliver the greatest impact relative to cost.

In practice, this creates difficult trade-offs. Where supplier emissions data is incomplete or inconsistent, procurement teams often take conservative decisions – favoring higher-cost or lower-risk options to protect compliance, delivery, or reputational exposure. In other cases, decarbonization targets collide directly with availability constraints, forcing teams to choose between carbon ambition and execution certainty.

We increasingly see procurement pulled into these decisions without clear guidance on how to balance cost, carbon, and resilience. Without transparent data and aligned decision rights, carbon becomes a source of friction rather than a managed performance dimension.

The most advanced organizations are moving beyond blanket requirements. Leading procurement functions embed carbon considerations directly into category strategies, contracts, and supplier scorecards – integrating sustainability with commercial judgment and cross-functional decision-making rather than treating it as a parallel topic.

Where this integration works, procurement can actively shape supplier behavior, for example by prioritizing the most carbon-intensive categories, differentiating requirements by supplier maturity, and linking incentives to measurable progress. Where it does not, carbon accountability remains unresolved, and increasingly expensive.

Outlook

The energy sector’s procurement challenges did not reset in 2026 – they intensified and became more structural. Sovereignty, execution capacity, cost pressure, AI adoption, and carbon accountability remain unresolved, but the expectations placed on procurement have risen sharply.

Organizations that continue to transform how procurement operates – strengthening analytical capabilities, differentiating supplier strategies, and embedding procurement deeply into investment and operational decisions – will be best positioned to deliver resilient, affordable, and scalable energy infrastructure in the years ahead.

Get in contact with our Experts

Stefan Benett

Managing Director

Callum Phillips

Principal