Many procurement professionals struggle when entering intensive negotiations with their suppliers.

Negotiation Excellence

The 8 Rules of negotiation excellence

Companies that invest extensively in preparation for negotiations with their suppliers and develop a detailed negotiating strategy can achieve significantly better results. First and foremost, this requires a professional procurement team.

Many procurement professionals struggle when entering intensive negotiations with their suppliers.

Many procurement professionals struggle when entering intensive negotiations with their suppliers. Potential fears include the risk that they negotiate too hard, and their supplier walks away. In most cases, these fears are unfounded. Ultimately, it’s in the interest of both parties to do business together. Good preparation is the key to gaining confidence and the right mindset, because then you know what you can and deserve to achieve in negotiations.

The former US President John F. Kennedy said it a long time ago: “Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate.”

Successful negotiation preparation starts with the engagement of all relevant stakeholders within your own company. It’s important to have a workplace culture where various departments work together, because most

of the time it’s not only prices quoted by suppliers but also their technical capabilities, product quality, sustainability measures, geographical locations, and much more that matters to the business.

It falls to the procurement team to engage, for example, with the research and development department to understand their technical requirements, the production department to get a better sense of the timeline, and the sales department to estimate customer needs in terms of business volume. The procurement team needs to make sure that all these aspects are addressed during the negotiation and captured in the final contract with suppliers.

Good preparation also means that the procurement team conducts a thorough market analysis of both the company’s competitors and potential suppliers. When it comes to suppliers, it’s good to not only consider the incumbents, but also to assess other suppliers available on the market as it can help bring in competition and thus increase your bargaining power. It’s also important to be clear on each supplier’s strategic significance to the company and vice versa. If you are a small supplier’s main customer, this gives you a greater leverage than if you are a small customer to a large supplier.

Engagement of all relevant stakeholders within your company and comprehensive market analysis lay the essential foundation to define your business objectives. Objectives together with competitiveness of your business environment are what drives answers to questions that are crucial for a set-up of any negotiation strategy. For example: Clear objectives play another important role. They help your negotiation team stay on track and prevent frustration and other destructive emotions during negotiations. In general, emotions can be of help at the negotiation table, but only if they are used proactively. Reactive, uncontrolled emotions can prevent you from engaging productively with your suppliers and may lead to an outcome that everyone is unhappy with.

Game theory is a study of strategic interactions, and negotiations are a prime example of those as their outcome depends on the interdependent decisions made by the negotiation teams of both parties. Indeed, offers and counteroffers, arguments and counterarguments, acceptances and rejections are decisions made by these teams that clearly affect the outcome, and an agreement can only be reached if everyone accepts the final terms.

Game theory provides a framework to analyze your leverage strategically and find the optimal way to apply it. For example, the bigger the business you have to offer to suppliers, the stronger your position in negotiations becomes. That’s why strategic bundling of upcoming new business opportunities can play in your favor.

Timing in general has a crucial strategic role. As another example, if suppliers’ existing contracts are coming to an end, they are in urgent need for business which puts them in a weaker bargaining position and means a great time to negotiate for you.

Game theory can help you take suppliers’ perspective, anticipate their reactions to the offers you might make, and in the end make offers that achieve the most favorable outcome. It’s also about tailoring your negotiation strategies to your specific needs and requirements in given circumstances. Last but not least, it prompts you to think about how you can change those circumstances, for example, by making changes to your negotiation team to make a favorable shift in negotiation dynamics.

Look for best response

Your offer must be realistic. How the other party will respond to your offer depends on what will be best for them in given circumstances and not on what will be best for you.

Think from the end

Before deciding on your offer, it’s important to think through all potential proposals. As the outcome will depend on the other party’s response to your offer, only by thinking about consequences of each proposal will you know which one is the best for you.

Change the game

You should always try to look for ways to improve negotiation dynamics. When the best possible outcome isn’t good enough, changing the current circumstances by postponing negotiations, choosing a different approach, etc. is the only way to make it better.

Where two or more eligible suppliers for the business are able to make offers, there’s a wealth of opportunities when it comes to negotiation approaches as the procurement team is then in the strongest position to set the rules of the negotiation game.

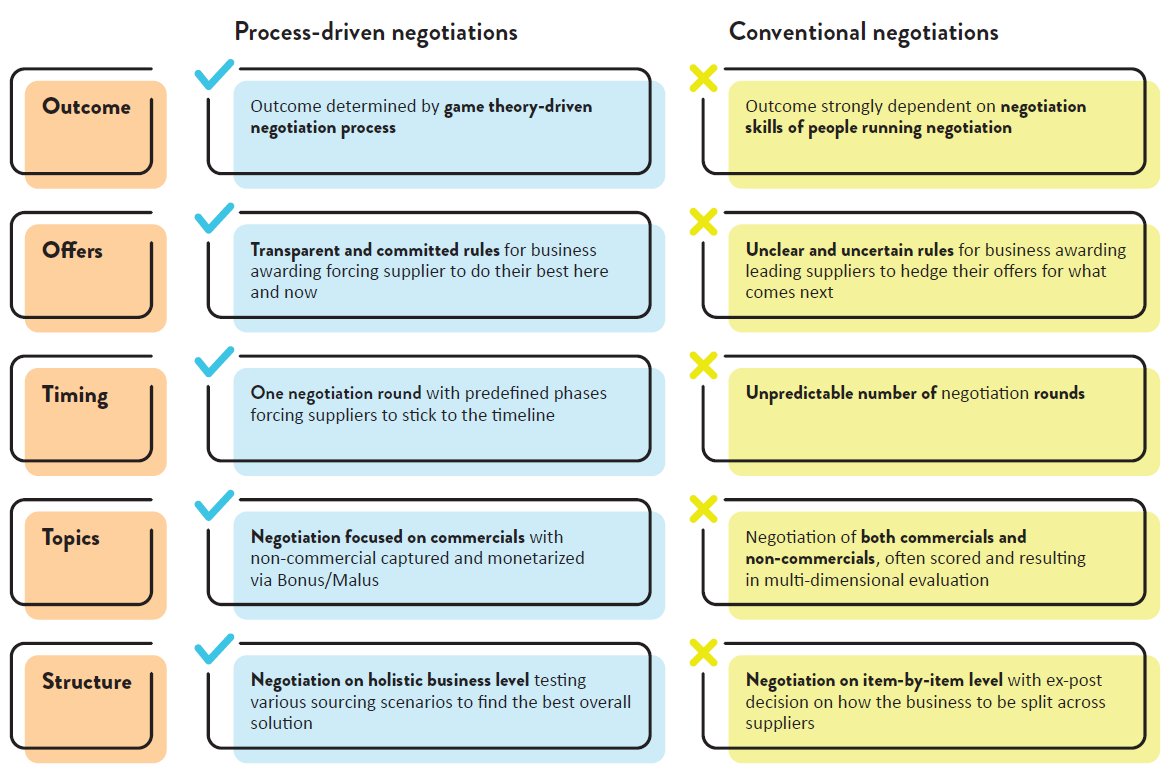

Approaches range from conventional negotiations with one-on-one discussions with each eligible supplier to auctions, or even e-auctions, and thus include process driven negotiations, which incorporate the best of the two extremes.

Key advantages of auctions are transparency of, and commitment to, the negotiation process.. That ensures that suppliers do their best within the predefined process, because there’s no other way for them to win the business.

However, there are also some issues that cannot be addressed in auctions and may argue for traditional one-on-one negotiations. These include the scope for customization to meet the needs of the business and the requirements of stakeholders, as well as the opportunity to emphasize and honor business partnerships.

Process-driven negotiations are built on the insights from mechanism design, which is a branch of game theory that focuses on developing incentives for everyone involved to achieve the desired objectives. They are characterized by a predefined number of phases, with clear rules on how each of these phases would unfold and how suppliers can win the business.

Depending on requirements, the negotiation phases can be run as auctions, be it English, Dutch, or any other type. They can also be windows of opportunity for exclusive one-on-one discussions with incumbents or strategic partners, invite incentivized requotes, for example, against strategically chosen target lines, and many more. The exact structure of the negotiation phases as well as the order in which they take place are always tailored to the business situation at hand and ensure that suppliers not only have to, but also want to do their best.

![]()

➔ ➔ ➔ ➔ ➔

Competition meets collaboration: Competitive spirit is an intrinsic part of negotiating. It turns negotiating into an exciting process – or even a game. As a rule, however, the “players” in negotiations do not have all the information, they are not aware of the full extent of the other party’s interests and do not know what they could still offer or what might be of interest to the other party, and vice versa. That is why the spirit of cooperation is invaluable. Thinking collaboratively will help you to get what you want as you give others what they want.

Remember, companies are made up of people: It’s as simple and as complex as separating the private and professional parts of everyday life. Businesses are led by people, but if things get personal rather than stay professional, particularly during tough and possibly heated negotiations, people might get into fight-or-flight mode. This stops them from thinking rationally, makes discussions unproductive, and can ultimately damage business relationships. Being tough on business topics but considerate and respectful with people you are negotiating with will help you get what you want and need.

Choose empathy: Negotiating can be an emotional business. You might think you have to choose between being tough and detached to keep a clear head in negotiations, or being sympathetic to the other party and their feelings, if you want to reach an agreement, but it’s not the only choice. You can also choose empathy. It will allow you to assert your interests without being too harsh and to show understanding of the other party’s feelings without having to feel the same way.

Be proactive rather than reactive: It’s important to prepare for all potential courses of action if you want your negotiations to succeed. It’s not only about having a plan of action but also about being proactive in preventing unfavorable developments and in steering negotiations in the right direction. The right trade-offs, the right people, the right timing and the right approaches are the key to success. Thorough preparation will help you to establish what “right” means in your business situation.

Never lie:There are many reasons why lying is a bad idea. It’s hard to keep track, both of the bigger picture and of the consistency of your claims. You will look foolish if your lies are discovered, because there’s no easy way to justify them. It’s a tempting strategy in the short term but detrimental to your reputation in the long term. You might feel you either have to tell the truth or lie, but that’s not actually the case – you can simply decide not to share everything.

It’s almost impossible to impose a negotiation process in a monopolistic situation – just think about Coca-Cola in retail, Microsoft or Google in the IT world, etc. It doesn’t mean that you can’t have successful negotiations with brands or other monopolists, but it does mean that your negotiation outcome depends a lot on your negotiation team’s creativity and ability to think outside of the box toward finding a win-win solution in your business situation.

Coca-Cola and Pepsi often have exclusive deals with retailers and aren’t placed next to their competitors. Shelf space and instore position, proximity to competing brands and copycats, and discount programs – all play a big role in retail negotiations and can provide leverage and help reduce prices. In the IT world, license combinations and contract lengths are key discussion points next to prices. There might also be an option to help development of smaller suppliers and thus create a tangible threat to current incumbents. This is something that’s currently happening in the OEM world, as the switch to electric vehicles puts traditional powertrain suppliers on an equal footing with new suppliers that have managed to get financial backing from OEMs. Creativity can be sparked by proactive listening, which is sometimes undervalued. Asking suppliers what they need and how they see the future business relationship with your company as well as analyzing past experiences with them can help you with ideas for the win-win outcome.

Creative application of negotiation tactics plays a significant role here as well, because they have a direct effect on people’s emotions and behavior, and one-on-one negotiations are characterized by intensive human interactions. In general, how people are wired as human beings and how they are brought up by society are what drives their emotional reactions and their behavior. Sometimes people react intuitively, which is why you can influence others and they can influence you. This means that understanding human psychology is crucial to successfully apply or resist negotiation tactics and in the end, to have successful negotiations.

Irrespective of how you negotiate, it’s the procurement team’s responsibility to drive negotiations, ensure the presence of the relevant stakeholders at the negotiation table, and achieve the best possible outcome for the business. Even though no two business situations are ever the same, any negotiation has three distinct stages – beginning, bargaining, and end.

At the beginning, the focus should be on gathering as much information as possible and on understanding suppliers’ interests to identify what available leverage to use and how to use it to achieve the business objectives.

Next comes the bargaining stage, which might have several phases focused on specific topics and in which both parties exchange offers and counteroffers as well as arguments and counterarguments. It’s important to follow the prepared negotiation strategy, but also to be flexible and revise it in response to new information.

At the end, if an agreement is reached, the final terms achieved during the bargaining stage should be incorporated into the contract that should be signed by relevant people from your company and the supplier.

Your negotiation team must be aligned on the focus and on the negotiation strategies for each of these stages. One of the best ways to do so is wargaming the developed strategies, in which everyone involved roleplays planned actions. It’s also a great way to see what would work and what wouldn’t.

Game theory and its decision trees are particularly helpful for the development of the negotiation strategies, especially during the bargaining stage. They help you to anticipate the ways in which negotiations could unfold and prepare for what would be the best course of action. This has a direct effect on the negotiation success, as it enables your negotiation team to be proactive rather than reactive during the intense time at the negotiation table.

Whether stakeholders from other departments but procurement should have a seat at the negotiation table or only play a role in the background depends on the business situation at hand. But in any situation, everyone who has a say in the negotiation outcome must be aligned, because it’s the only way to avoid surprises and derailments during negotiations. A better outcome may be reached even with an imperfect strategy if everyone is on the same page than if a perfect one is forced on a team that isn’t aligned.

Once a negotiation ends, another one begins. This is not only because business opportunities tend to come in waves but also because the result of one negotiation sets a benchmark or a starting point for the next. Furthermore, procurement departments are in regular contact with their suppliers, and daily discussions are mini negotiations of their own.

And the world is small – people switch companies but tend to stay within the same industry. What will rush ahead is their reputation as a negotiator and business partner, not the specific results achieved during a negotiation. What will also rush ahead is a company’s reputation when it comes to negotiations. Negotiation principles and company’s values could help build the reputation you would like to have for your company, even when things get tough. Short-term gains in negotiations might seem important, but it’s the long-term implications and relationships with suppliers that have a real impact on the future.

Barry Nalebuff has been a Professor at the Yale School of Management for over 30 years, where he teaches negotiation strategies and game theory. Alongside his academic work, Nalebuff founded drinks brands Honest Tea, Kombrewcha, and Just Ice Tea. He later sold the first two businesses to Coca Cola and AB-InBev. His new book on negotiation is called Split the Pie.

Professor Nalebuff, you believe that many negotiations aren’t handled right. How so?

Most people don’t know what they’re negotiating about – and that’s where the problem begins. We need to find out what the negotiations involve and then discuss how to split the gains fairly.

Let’s assume we’re not negotiation experts. What exactly is the “negotiation pie”?

I’ll give you an example. Imagine two people. Person A has EUR 5,000 and can get one percent interest on this amount, i.e. EUR 50. Person B has EUR 20,000 and can get two percent interest, i.e. EUR 400. Together, they could get three percent interest on their combined amount of EUR 25,000, i.e. EUR 750.

What figure makes up the pie? The EUR 750, surely?

No – that’s the mistake most people make. In reality, it’s all about the extra amount that each person receives as a result of joining forces. Previously, they would have received EUR 450 in total; now, it’s EUR 750. So the pie is only this EUR 300 difference and this is what needs to be divided equally. That’s unfair though. After all, person B has invested four times as much initial capital in the deal.

Yet the extra EUR 300 is only achievable when they both invest together. Both parties are equally needed, so both should get the same amount.

It’s hard to believe that the stronger party in the negotiation would agree to a deal like that.

It’s wrong to equate strength with size. Just because, as in our example, one side has more capital, that doesn’t mean that they’re actually stronger. I’ll give you another example, this time taken from a real scenario. My mother’s landlord wanted to sell the house my mother lived in. He offered her the chance to buy the house before he officially put it on the market. By doing so, he wanted to save on the estate agent fees. My response to him was that my mother should receive half of this cost saving because, if she were to refuse, he would have to pay an estate agent the full amount anyway. He accepted the argument.

Okay, that’s understandable so far. But what do we do when the pie is less clear-cut?

Often, the true benefit of a deal is only clear in retrospect. In that case, there’s nothing wrong with determining the pie afterwards. We can agree in advance how we’re going to split it – e.g. fifty-fifty – But we’ll only know what we’re dividing up after a certain amount of time has passed. There are plenty of examples of this, too.

We’re intrigued, tell us more.

A few years ago, I founded the company Honest Tea together with a former student of mine, Seth Goldman. A little while later, Coca-Cola wanted to acquire our business, but it was clear that our company wasn’t really big enough yet. We agreed to complete the sale in three years’ time. Until then, Coca-Cola would support us with production, sales and procurement.

Of course, Coca-Cola didn’t want to pay more just because we had grown with their help. So we agreed with them that they would pay in full for the production volume that we could achieve on our own but only pay half for everything above that. The same principle applies, you see – while it’s true that Coca-Cola is a bigger company, the deal wouldn’t have come about in the first place without us.

Doesn’t that simply kick the can down the road? Ultimately, the parties still always need to agree on what is and isn’t additional profit?

Of course, there can still be differences of opinion. Either way, however, we have changed one fundamental thing: we have transformed the negotiation into data analysis. We may discuss what data forms the basis for the negotiation or what the data means, but we are no longer talking about fair splits. I’ve been accused of thinking like Mr. Spock from “Star Trek” because I like to approach negotiations from a purely logical perspective. To be honest, I find it strange how little logic tends to feature in negotiations.

Doesn’t that create new issues though? Businesses could be tempted to keep back data so as to manipulate the pie to their advantage?

That can be a problem so it’s crucial to clarify how to negotiate as soon as the negotiations begin. Of course, the “Split the Pie” method only works if both sides are willing to participate. At the start, I therefore need to clearly communicate to my counterpart that my aim is to work together and get the biggest possible pie for each of us. If we agree on this, I can then also expect and demand a certain level of transparency. This worked well in our negotiations with Coca-Cola; they had much better data than us, of course, which they shared with us.

At the end of the day, we still rely on the other side being honorable though, don’t we?

Yes, that’s true to a certain extent but it’s also in that party’s interests to create a reasonable data base. For example, I was once asked to advise city authorities on negotiating an airport rental agreement. In all honesty, I knew nothing about how an airport works from an economic perspective, so I asked the operating company to provide me with their data. After all, I ultimately had to give the mayor a recommendation. Without data to back up the decision I wasn’t prepared to recommend to the mayor that we were being offered a fair deal.

What do we do if our negotiation partner is opposed to the “Split the Pie” method?

If that happens, you have to accept the situation and take a different tack. There are plenty of other negotiation tactics, including tricks and feints. I think it’s a shame but, while you can lead a horse to water, you can’t make it drink. Unfortunately, many people automatically try to build pressure into their negotiations, simply because it’s encouraged in our culture. In reality, nobody actually wants to deal with someone like that.

Matthias Schranner used to be a police negotiator; today, he advises politicians and businesses. He talks to us about the most serious mistakes when negotiating, the role your value system plays, and getting the timings absolutely right.

Mr. Schranner, during your time in the police, what was your toughest case?

I was involved in a hostage situation. I was in the same room as the kidnapper; no barriers, no SEK team [the German Special Task Force]. The kidnapper had a gun in his hand and said “Outside – or I’ll shoot the hostage.” That in itself was a formative experience.

How did you resolve the situation?

I negotiated. The first thing you have to do in a situation like this is release the pressure. I told the kidnapper he was making the decisions and that he didn’t have to do so immediately. I assured him that he had control over the situation and was responsible for how it played out. Then, I offered him a deal: We’ll talk for five minutes and then you can decide. We started talking and I was eventually able to persuade him to relent, which gave me the crucial advantage.

Today, you advise politicians and businesses on deals that run into the millions. Are there parallels between the two situations?

We get called in to assist with extremely tough negotiations; for example, when there is only one supplier to negotiate with and failure is not an option. The same principles apply – we have to come to an agreement to prevent catastrophe. The principle of starting by releasing the pressure also applies in business negotiations, along with emphasizing the commonalities and shared history between the two parties. It’s also important to demonstrate a shared future to make it clear that both sides are interested in finding a solution. This is much more effective than focusing on the areas of conflict.

Why is that?

I can then state my demand; for example, a ten-percent price increase. Making this request forces my counterpart to respond, by either agreeing, saying “yes, but”, or saying “no” and explaining their reasoning. All three situations are good for me because they provide me with information that I can use to develop a mutually beneficial plan. For example, I could suggest implementing an incremental price increase over a period of several quarters to reach my goal. The mistake most people make at this stage is that they don’t ask; they start with a disagreement and argue.

Why do you believe arguing doesn’t work?

Arguments arouse people’s emotions, and emotions are never a good thing in negotiations. They focus the discussion solely on the point of disagreement and the past, refer to previous contracts, or encourage statements like “but you said that in the minutes last week.” This is fatal because there are only two options when negotiating – you either negotiate successfully or you end up being proved right. If I want to be right, I can take legal action. But if I want a solution, I have to negotiate – and this is when arguments don’t work because they result in justification and rationalization. What’s more, they almost always lead to the person you are negotiating with feeling attacked and, consequently, becoming emotional.

There are two reactions to this, too. Either your counterpart totally overreacts, becomes stubborn, and goes on the attack, or they completely withdraw into themselves and disengage from any negotiation.

If the person I am negotiating with becomes emotional, what can I do to take the emotion out of the situation?

When people become emotional, it’s always because they feel threatened, so you need to remove the risk of this happening and bring the discussion back to commonalities. You can highlight what you’ve already gone through together and emphasize that this situation, too, can be resolved. It’s very important to continue to negotiate, however, because taking a break at this point would be a mistake. This gives people the opportunity to talk to allies who validate them; the next day, the two sides will then simply be further entrenched.

There are hundreds of books that recommend psychological tricks when negotiating. What do you think about that?

It’s not a strategy I rate. We’re not here to play psychological mind games – those are misleading tricks for beginners that don’t actually add anything. The same applies to the outmoded image of the

“bad cop” who comes in threateningly and hammers on the table. Professional negotiators no longer act like this – at least not in the league we operate in, which involves deals worth many millions of euros.

If I find myself opposite a professional negotiator, is that to my advantage?

That’s a huge advantage. Novice negotiators often get to a certain point and then don’t know what to do – and this uncertainty leads them to become emotional. Then they start to issue threats, which

is incredibly frustrating for a professional negotiator like me. When both sides negotiate professionally, reaching a good outcome will happen much more quickly. I’d even go so far as to say that the more professional the two sides are, the better the result. The better your opponent, the better you will play the game yourself; we all know this from the world of soccer. A club facing a top Champions League club will play at a completely different level than when they face a club threatened with relegation in their own league. If the other side is really good at their job, it usually makes it much more fun, too.

It sounds as if you like to win when you negotiate. You probably don’t believe in the Harvard win-win method, do you?

It’s commonly understood that a win-win situation means both sides achieve a good outcome. What many people forget, however, is that this only works when both parties espouse the same value system and are looking for a win-win outcome. When I enter negotiations in the spirit of cooperation and make a suggestion that sounds fair to me but my counterpart rejects it because their values are very different to mine, I get disappointed. This then puts me in an extremely tricky position because emotions come back into play. Especially in German-speaking countries, many people make this mistake and shy away from conflict. They start the conversation with what they consider to be a “fair” offer and thereby try to get the negotiation out of the way. The concept is often associated with bargaining, as if negotiating were a bad thing. Of course, this mindset is not the way to achieve the results you’re looking for.

Is it different in other cultural settings?

There are a number of differences that come into play here. In the USA, for example, negotiators enter into a negotiation with more pressure. They see it as a game and are aiming to win. If you start cooperating too early on, you’ll be walked all over. There is only one solution to this – launch a full broadside in response. If my counterpart says +10, I’ll say -20 on principle. Then the Americans know the game has begun. Don’t misunderstand me; this is purely about strategy rather than tone – we always remain extremely polite.

If we look at China, how is negotiating there different?

In China, negotiators also treat the negotiation as a sort of game. The word “cunning” often has negative connotations in our culture; we say someone is as cunning as a fox. In China, however, it suggests shrewdness, so you either reveal nothing of your intentions to your counterpart, or only give them incomplete information. This is neither “good” nor “bad” but simply an alternative way of doing things. However, you do of course have to be aware as a negotiator.

You say you shouldn’t offer to cooperate too early on, yet, on the other hand, you talk about having to find a shared solution. How do you pinpoint the right time to cooperate?

One of the most common mistakes is to start the negotiation by putting forward a potential solution straightaway and presenting a finalized offer. Initially, the crucial thing is to bring clarity to the negotiations. First, you have to be certain there are no more misunderstandings. What does the person I’m negotiating with understand by “long-term” or a “reasonable price increase”? There’s no point entering the cooperative phase until any potential misunderstandings have been ironed out. Once everything has been clarified, that paves the way for each party to state their demands and work together to find a solution. You have to develop an instinct for judging the right time to do this. The more negotiation experience you have,

the easier it becomes.